Beginnings

P. L. Dunbar Middle School for Innovation (DMS) is located at 12th and Polk streets. DMS is named for Paul Laurence Dunbar, a distinguished and gifted African-American poet and a precursor to the Harlem Renaissance. Our school buildings and campus have a rich and diverse history in the community. The original name of the school, Dunbar High School, still remains engraved in marble on the central building. Our campus is comprised of three attached buildings. The Mozee building houses primarily sixth grade students. The Central building houses the main office, nurses office, full gymnasium and PE department, a 900 seat auditorium, music classrooms (band orchestra and chorus), communications studio and WDMS TV station, and full cafeteria. Seventh and eighth grade classes, counseling suite, library, and technology classes comprise the West building. The Amelia Pride Building, originally the home economics center for girls, now houses several alternative and adult programs.

Dunbar High School opened its doors to students in 1923. The school represented the fulfillment of a request by the black community to the all white school board to create a new black high school. In the early years, the Dunbar faculty and administration were primarily white. The curriculum then reflected the classical tradition. In order to graduate, a student had to take four years of English, Mathematics, History, Science and Latin. The curriculum was extremely successful in preparing graduates for college. As many as 90% of the students in the graduating classes from the 1920s enrolled in college.

However, the classical curriculum had little appeal or relevance to large numbers of high school aged blacks. Only two generations out of slavery and living in a rigidly segregated community, many teenaged blacks were economically unable or insufficiently motivated to attend high school. In the beginning, Dunbar High School was a school for a small, elite group of students whose parents recognized the value of formal education and had the means to see that their children took advantage of it.

The decade of the 1930s was a period of rapid change for Dunbar High School. While the school remained under the authority of the all white school board, the positions of leadership and authority within the school were gradually occupied by blacks, including that of the principalship. Clarence Williams Seay, who had first come to Dunbar as a teachers and coach, returned to the school in 1938 as Dunbar’s principal. He filled that position until his retirement in 1968, a 30 year period of dynamic leadership which saw the institution achieve academic excellence in spite of segregation barriers.

At the heart of the “community school” concept was the goal to create a program and mold a staff that could meet the needs of all the black youth in Lynchburg and at the same time offer cultural, athletic, and educational programs to the entire community. One of Mr. Seay’s most important steps was to actively recruit the best qualified teachers and administrators available. Recruiting trips were made throughout Virginia and surrounding states.

With a larger and more diverse faculty, the curriculum at Dunbar was expanded. The established classical program became the college preparatory programs and was joined by more general and vocationally oriented programs in such areas as clerical studies, commercial foods, home economics, and the mechanical and building trades. With this expansion of the curriculum and increasingly larger number of Lynchburg teenagers entered high school and graduated. Accreditation for the expanded curriculum was achieved by the 1950s.

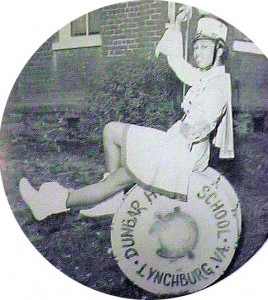

In addition to the growth of the academic program, the 1930s were characterized by significant growth in extra-curricular activities. Dunbar became the focal point for the entire black community. Black families came to hear the Dunbar choir, or attend sporting events such as football and basketball and eventually tennis and track events, or to see plays or to take part in the Hippodrome.

The rapid growth of the 1930s was accompanied by the need for additional financial support. With little additional support available from the school board, the black community accepted this responsibility. In 1934, black citizens formed the Dunbar Parent-Teachers association. The PTA was to play a vital role in the life of Dunbar High School. Some of its members remained active in the organization from its inception until its demise in 1970.

As Dunbar High School entered the 1940s, not even a World War could overshadow the great advances that were being made at the school. When the war ended in 1945 and the country returned to peacetime status, Dunbar began its “golden age.” This period of remarkable achievement and community pride was to last well into the 1960s. Those were the years of new buildings at Dunbar, the years of national and state championships in athletics. Dunbar graduates were going on to college at the nation’s most prestigious schools and achieving positions of local, state, and national prominence. Dunbar graduates could be found as leaders in areas such as medicine, law, education, civil service, the arts and athletics. Those were the years of homecoming parades through the center of Lynchburg and senior proms in the gym. Dunbar had firmly established itself as a “community school” and had become a vital and cherished institution with in the black community.

Until the late 1940s the Dunbar Library was a “branch” of Jones Memorial Library, a private, segregated institution. The Dunbar “branch,” under the leadership of Mrs. Anne Spencer, received the books which had be discarded by Jones Memorial. Dunbar students were not permitted to borrow books directly from the Jones Memorial Library. In 1946, the PTA took responsibility for raising money for a school library.

In the 1940s and 50s Dunbar High school was still a racially segregated institution. Throughout its history the students and faculty recall very little contact with the white community of Lynchburg. The City of Lynchburg as a whole remained a segregated community. Dunbar teachers recall counseling many of their students to seek jobs and make their lives in the less segregated cities of the northeast. It was widely recognized among blacks that there were limited opportunities available to them in the Lynchburg economy. Some Lynchburg residents, both black and white, view this forced exodus of many of the brightest young blacks as one of the greatest tragedies of segregation. For Dunbar graduates, Washington, D. C., was the most common destination.

The 1954 Supreme court decision did not bring immediate change to Dunbar High School. Those at Dunbar in 1954 remember receiving word of the decision and feeling a sense of victory. But there was no expectation of immediate change and none came. It was not until the early 1960s that the 1954 Decision was felt in Lynchburg as a consequence of a lawsuit filed by members of the black community. Virginia had resisted desegregation as long as possible. Within the black community the debate over desegregation was sometimes bitter and from some the consequences painful. To achieve the goal of desegregation put the existence of Dunbar High School in jeopardy. Some blacks favored the transfer of black students to the white school. Others argued that desegregation could be achieved by bringing whites to Dunbar. The decision which was finally made resulted in the end of Dunbar as a high school in 1970.

The School for Innovation, 1994

Dunbar became a school for innovation in 1994 and was renamed Paul Laurence Dunbar Middle School for Innovation. The implementation of this initiative was enabled through awarding of the Magnet Schools Continuation Grant. Since then, the Lynchburg City School system, with support of the School Board, has continued this endeavor.